Considering the developments in commerce and electronics over the last 50 years, I am convinced that no other generation but ours could have known how the prophecy of the number 666 would be fulfilled. The technology necessary to bring it to pass simply had not been developed or conceived of before our day. Therefore, the understanding necessary to interpret John’s prophecy in Revelation wasn’t available until only very recently. However, in precisely the same time frame that Electronic Funds Transfer and Smart Cards have come on the scene, there has also arisen a concurrent technology at the retail level which will ultimately allow the coming Cashless Society to function smoothly. It is this one development that will become the final key to integrating the Mark of the Beast with the Number of the Beast. This invention also digitally links potential buyers with the items that are for sale in an electronic financial system. This is important to understand, because in order for the Antichrist’s system to work, digital money must be connected to the digital identification of people and things. This allows the entire economy to be electronically linked and identified through a system of marks. This whole scenario as it applies to physical products being sold revolves around something called barcode technology, which is being used to provide each item with its own unique mark, just as the Antichrist will demand that each person receive his or her own unique mark.

Considering the developments in commerce and electronics over the last 50 years, I am convinced that no other generation but ours could have known how the prophecy of the number 666 would be fulfilled. The technology necessary to bring it to pass simply had not been developed or conceived of before our day. Therefore, the understanding necessary to interpret John’s prophecy in Revelation wasn’t available until only very recently. However, in precisely the same time frame that Electronic Funds Transfer and Smart Cards have come on the scene, there has also arisen a concurrent technology at the retail level which will ultimately allow the coming Cashless Society to function smoothly. It is this one development that will become the final key to integrating the Mark of the Beast with the Number of the Beast. This invention also digitally links potential buyers with the items that are for sale in an electronic financial system. This is important to understand, because in order for the Antichrist’s system to work, digital money must be connected to the digital identification of people and things. This allows the entire economy to be electronically linked and identified through a system of marks. This whole scenario as it applies to physical products being sold revolves around something called barcode technology, which is being used to provide each item with its own unique mark, just as the Antichrist will demand that each person receive his or her own unique mark.

It is amazing how many fulfillments of end times prophecy have had their rudimentary beginnings back in the decade of the 1940’s. In the very same ten-year period that Israel became a nation, European integration got its start, and digital electronics and computer development began, we also find the beginnings of barcode technology, which would be destined to bring into being the Number of the Beast.

The Development of Product Identification

We have already seen how important it is becoming to the Empire-Beast to validate the identity of people as our economy is moved toward an increasingly cashless society (see The Identification Problem). Ensuring proper identity is also being extended to things as well as people. This includes the identification of every product that is bought or sold along with virtually every other item that humans use or interact with. This is being made possible in part through barcode technology.

In October of 1949, Norman Woodland and Bernard Silver of Philadelphia submitted a patent entitled, “Classifying Apparatus and Method” (US Patent 2,612,994, issued 1952). It described a technique of labeling manufactured articles with tags containing certain patterns of lines or colors. These patterns could be coded with special classifications depending on the product to which they pertained. They envisioned that the code would then become a unique identifier for each item being tagged.

In their patent, Woodland and Silver described how a series of white lines on a dark background could be used to carry this encoded data. The spacing and thickness of the lines within the pattern could be interpreted as a particular number sequence for the identification of a product. Special illuminated scanners could be used to read the data contained in the bars as a tagged article was interrogated. Items marked with the code could then be automatically registered and the data maintained by a computer, which was networked to the scanning device. According to Russ Adams writing years ago in Bar Code News, the first scanners “consisted of a transparent conveyor belt onto which the package was placed, symbol side down” (Bar Code News, Mar./Apr., 1986). Strong lights that were pointed up at the code reflected the pattern back down into a photosensitive detector. Tiny fluctuations in the amount of light energy reaching the detector would result in small variations in an electric current, which then could be correlated to the barcode pattern being read. These electrical signals would thus be interpreted as product or item numbers representing the encoded information stored within the barcode pattern. The digital data could then be used for computerized inventory control or any other application that might be helped through automated identification.

In their patent, Woodland and Silver described how a series of white lines on a dark background could be used to carry this encoded data. The spacing and thickness of the lines within the pattern could be interpreted as a particular number sequence for the identification of a product. Special illuminated scanners could be used to read the data contained in the bars as a tagged article was interrogated. Items marked with the code could then be automatically registered and the data maintained by a computer, which was networked to the scanning device. According to Russ Adams writing years ago in Bar Code News, the first scanners “consisted of a transparent conveyor belt onto which the package was placed, symbol side down” (Bar Code News, Mar./Apr., 1986). Strong lights that were pointed up at the code reflected the pattern back down into a photosensitive detector. Tiny fluctuations in the amount of light energy reaching the detector would result in small variations in an electric current, which then could be correlated to the barcode pattern being read. These electrical signals would thus be interpreted as product or item numbers representing the encoded information stored within the barcode pattern. The digital data could then be used for computerized inventory control or any other application that might be helped through automated identification.

Even with its obvious potential for streamlining many manufacturing operations, for the first thirty years after it was described the science of barcodes was barely known outside of those specialists working within the obscure industry itself. By the late 1950’s, the entire market for barcode technology amounted to less than $100,000 in annual revenues. Its use, however, grew in direct proportion to the availability of inexpensive scanners and computer systems that could read, store, and process the data. Little did Woodland and Silver realize the great impact that their invention would eventually have on our society decades later when computers were ubiquitous and everything was being marked with a digital ID.

In fact, twenty-five years later as a result of microprocessor technology becoming widely accessible (see The Cashless Society on the development of microelectronics), barcodes began to proliferate like wildfire through the decades of the 1970s and 1980s. The grocery industry actually designed and pioneered the use of modern barcodes to identify every food item sold. Food retailers thus became among the first to institute scanning devices into checkout counters to facilitate the rapid itemization of purchases. What used to be a laborious manual operation to ring up every item in a person’s cart using price tags affixed to each one suddenly became just a matter of swiping each product’s barcode over the laser scanner to tally the products and prices. Not only did barcodes eliminate the error-prone manual entry of prices during checkout, but it also eliminated having to price each product on the shelves with price tags. In addition, using barcodes the prices on products could be changed at any time without having to remark each one with a new price tag. The new price need only be changed in the computer database that correlated the barcode ID and product with its price, and when that item was registered during checkout, the new price would be automatically charged. Inventory levels also could be automatically registered in computer databases without having to manually count each item on the shelves.

Another field to experience the impact and advantages of barcodes was the manufacturing industries. It was quickly found that barcodes could provide the means to totally automate inventory control, receiving operations, warehouse storage and retrieval, monitoring and control of work-in-process, sorting operations, analytical testing, assembly operations, billing systems, tracking of documents, baggage handling, data entry, and the list of applications could go on and on. Today, virtually every major industry is using barcodes to maintain inventory and manage material flow.

Of all the related techniques one might imagine for identifying and recording data related to specific items (i.e., manual entry systems, magnetic stripes, or optical character recognition), barcodes have proven themselves to be incredibly versatile and reliable. According to published statistics, having a person manually type data into a computer terminal will cause a minimum of one error in every 100-300 keystrokes (much more if it was someone like me doing the typing!). By contrast, using barcodes to enter data, the error rate can be reduced to one character in every 300 million characters scanned (Bar Coding and Productivity, by Computype, Inc., p. 5).

Accu-Sort Systems, Inc., a major supplier of scanning devices said,

“One of the primary advantages of barcodes over other technologies is its low susceptibility to misreads. Expensive magnetic inks, similar to those used by the banking industry, are not required to print the symbol. And unlike magnetic stripe identification, bar code symbols are impervious to electromagnetic interference often found next to conveyors and on the factory floor”.

As a result of these advantages, barcodes can now be seen being used almost everywhere. Companies that use them in manufacturing processes usually have a code affixed to every piece of raw material going into their products. For instance, the automobile industry uses the capabilities of barcodes to completely automate their assembly line operations. Since each auto part can be scanned and recorded in a central computer, the companies can know exactly how much inventory is present, when to order another piece, and precisely when to send an item to the assembly floor. Barcodes make this type of just-in-time manufacturing processes possible. In addition, virtually all manufacturers are now providing finished goods with a final code for use at the retail level for customers to purchase products. In this way, all stores can completely automate their own inventories and dramatically speed up operations at the checkout counter. The giant retailer Walmart was one of the first stores to require barcoding of products by all of their suppliers, and they quickly installed laser scanners in checkout lanes to facilitate rapid item entry for purchases. After Wal-Mart switched over to barcodes in the early 1990’s every other retail company followed suit. In fact, today virtually every product you can buy has a barcode printed somewhere on its packaging ready to be scanned and used in automated systems at the point of sale (POS). But that’s not all. In an advertisement for ID Expo, an international conference on barcode technology, it was stated,

“Automatic identification systems can be used in countless applications outside of retail stores and factories—in banks, hospitals, insurance companies, telephone companies and railroads. In fact, almost anything that can be counted, packaged or tracked can be bar coded”.

The technology of barcoding has become so inexpensive that now virtually anyone can make use of it—from the smallest entrepreneurial company selling products online to the largest global corporations—and all due to the advances in computer and label printing systems, which make barcode identification quick and easy. An entire system can be fashioned using only a personal computer, an ink jet or laser printer, and a special software program—which can even come complete with a simple hand-held scanner—and you’re ready in no time to use barcodes in any number of applications.

Coding Symbologies

So how does all of this technology relate to the development of the Antichrist’s economic system and to the mysterious number 666? To discover this relationship, it is first necessary to understand the digital makeup of barcodes and the coding symbologies that are used to create them.

So how does all of this technology relate to the development of the Antichrist’s economic system and to the mysterious number 666? To discover this relationship, it is first necessary to understand the digital makeup of barcodes and the coding symbologies that are used to create them.

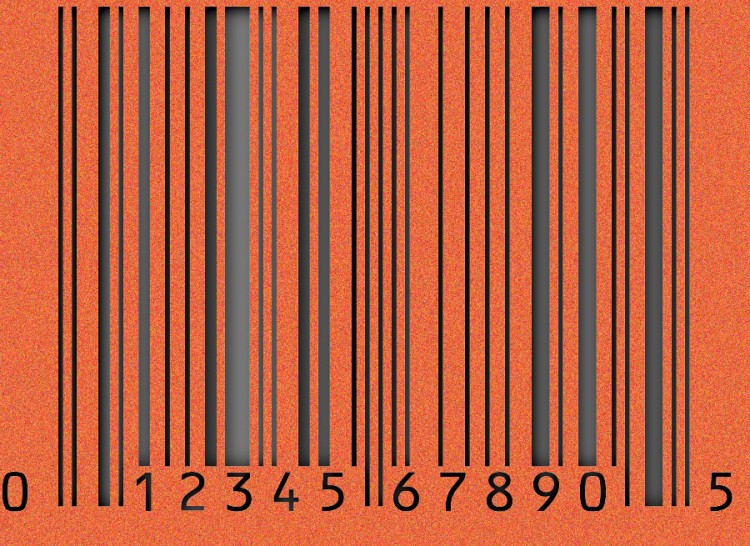

Although the anatomy of the barcodes used today all appear different than the original version described by Woodland and Silver in 1949, the basic concept is still the same. Instead of being white on black, however, they now consist of black stripes on a most-often white background. Their immediate appearance of seeming to be a bunch of bars, usually running vertically, gives them the universal name barcodes. However, the manner in which these bars are arranged is not as haphazard as it might seem at first glance. Each pattern follows specially defined design rules which vary according to the type of code being used and the number or letter sequences encoding them. Different applications of barcodes have resulted in many different “symbologies”, or ways to code for the data they contain.

Most of the barcode symbologies in use today have one underlying principle in common: each uses the combination of vertical black bars and white spaces to digitally encode particular numbers or characters. The letters or numbers hidden in the barcode patterns are decoded by a scanner and computer system when the symbol is read. Unlike the relatively crude scanners proposed by Woodland and Silver, modern scanners use very efficient red lasers and they can be handheld or mounted under the counter to accept product reading. Henry Petroski, writing for Science 81 magazine in the early days of the technology, described the process of reading a barcode. In this case, the application was for the retail market, but the principle is still the same today:

“A low-level laser continuously traces an intricate crisscross pattern that covers every square millimeter of a check-out window several times each second. When the concentrated beam of red light strikes the UPC symbol on an item of merchandise passing over the window, the widths of the black bars and the white spaces between them are reflected into the scanner and recorded as electrical impulses. The impulses are digitized, that is, translated into computer binary code. Just as an old-time wireless telegraph operator could pick out an S-O-S from background static, the automated check-out scanner can sense electronically a valid product code among the noise generated by the list of ingredients on a cereal box or the smile on a magazine cover” (Science 81, Jul./Aug. 1981, p. 80).

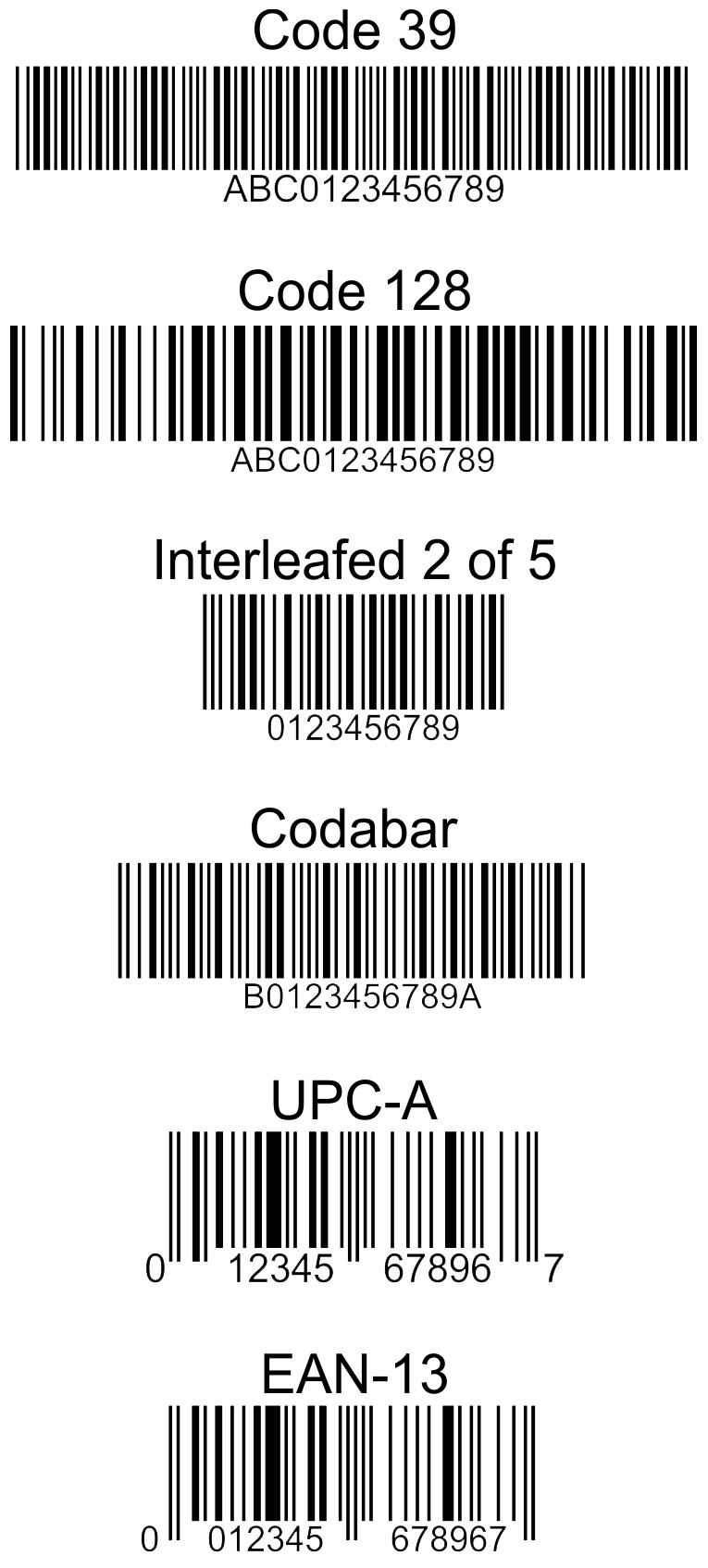

Some of the more popular barcode symbologies that have been developed go by the strange names of Codabar, Two-of-Five Code, Interleaved Two-of-Five, Three-of-Nine Code (or simply Code 39), and the Universal Product Code (or UPC, which is now a subset of the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN)). The appearance of these codes is all subtlely different from one another due to the different ways the numbers and characters are encoded in each symbology; however, the concept for digitally encoding information is all very similar among them. The following sections will review some of these major barcode types to provide a fundamental understanding of the technology underlying them. Then using this understanding, we will discover how these marks will be used in the final system of the Antichrist and incredibly, how a visual representation of the Number of the Beast has actually been designed into the most common barcode type that now marks all retail products.

Code 39

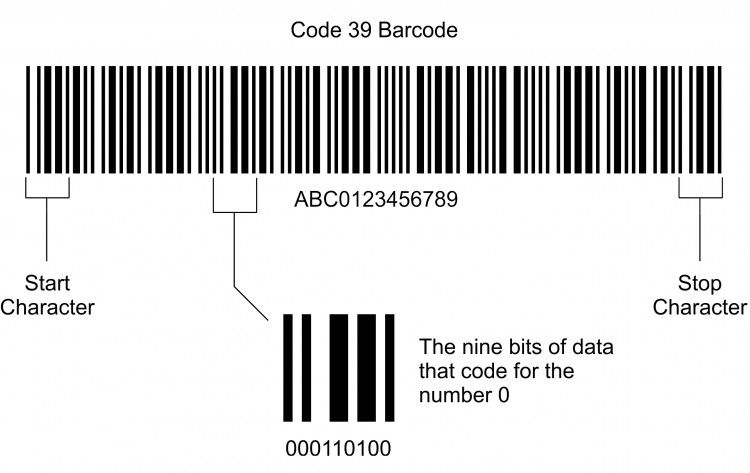

To understand the coding process, it’s best to start with a relatively straightforward code to interpret, such as the Three-of-Nine Code (or just Code 39). In Code 39 (see figure) each number or character is encoded by nine bits of information. The name comes from the fact that three out of the nine elements (or modules) making up each character or number within the code must be wide. The elements (or bits of information) are represented by the black bars and the white spaces in-between each bar. Therefore, each pattern that codes for a number or letter in the Code 39 symbology must contain a total of three wide black or wide white spaces out of the nine white or black spaces possible. The remaining six elements must be narrow bars or spaces. A black bar or a white space of one module wide can be seen as the narrowest bars within the code. If you can imagine 9 such modules coding for each number, then you can see the separation of each coded number within a barcode. Multiple black modules or multiple white modules occurring next to each other make up a wide black bar or a wide white space.

To make these patterns computer readable, the black and white regions first must be converted into the binary computer language of ones and zeros. For Code 39, this simply means that every number or letter has to have a nine-digit binary code which is made up of a series of zeros and ones. In this particular barcode format, each wide black bar or wide white space is interpreted as the binary digit 1. Conversely, every narrow black bar or white space represents the binary number 0. As a scanner sends information back to the central processor, the computer receives a string of these binary ones and zeros. This data is then matched to the assigned codes for each number or letter designated within the Code 39 format. Thus, according to these preassigned codes, the number 3 would result from the binary string 101100000 being read, and if the string 001010010 is scanned, the computer would immediately interpret that the letter p is meant. In this way, every letter and number in the Code 39 format has its own unique nine-digit binary code.

A complete barcode is built from a series of these binary strings placed all in a row as the entire barcode is read. Thus, one barcode in the Three-of-Nine format may code for ten or more different numbers or letters all on one symbol—each of the characters being made up of nine bits in a binary string. When the scanner reads the entire code, the computer automatically separates the binary information into nine-digit increments and then interprets the complete barcode ID. This ID can then be used to associate with and identify a particular product or raw material used in commerce.

In practice, each item tagged with a barcode would have its own unique number and letter combinations to identify it. The distinctiveness of every barcode mark would enable a computer to maintain proper inventory control or any other functions that correct item identification could allow.

Codes 39 as well as the Interleaved Two-of-Five variety were originally recommended by the Distribution Symbology Study Group as the main barcode standards for use on shipping containers. Accordingly, these symbols typically originate in the manufacturing industries and are placed on boxes or containers containing raw materials or products. Code 39 is by far the most common barcode used for items that do not cross POS (items not sold at retail). They are found on virtually all shipping containers and boxes for easy recording of product information. For routine processes, humans don’t even have to open a box or container to know the item or items within it—a barcode scan can automatically ID it and maintain a running inventory count of the items in a central database.

The Global Trade Item Number (GTIN) and 666

In perhaps the most important application of barcode identification, especially as related to Biblical prophecy, the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN) has become the universal standard for marking all retail goods at the point of sale (POS). This symbol has several different subsets that are used in different regions of the Western Alliance and in other countries around the world, but their similar design and identical symbology makes them compatible everywhere. The main GTIN barcodes consist of the Universal Product Code (UPC) which is used in the U.S. and Canada, the European Article Number (EAN; now renamed as the International Article Number) which is used in the European Union, and the Japanese Article Number (JAN) which is a subset of the EAN and is used in Japan. The JAN code is identical to the EAN code with the first two control numbers on the left designated as “49”. The complete EAN code, called EAN-13 has become the worldwide standard for barcode use on all retail products.

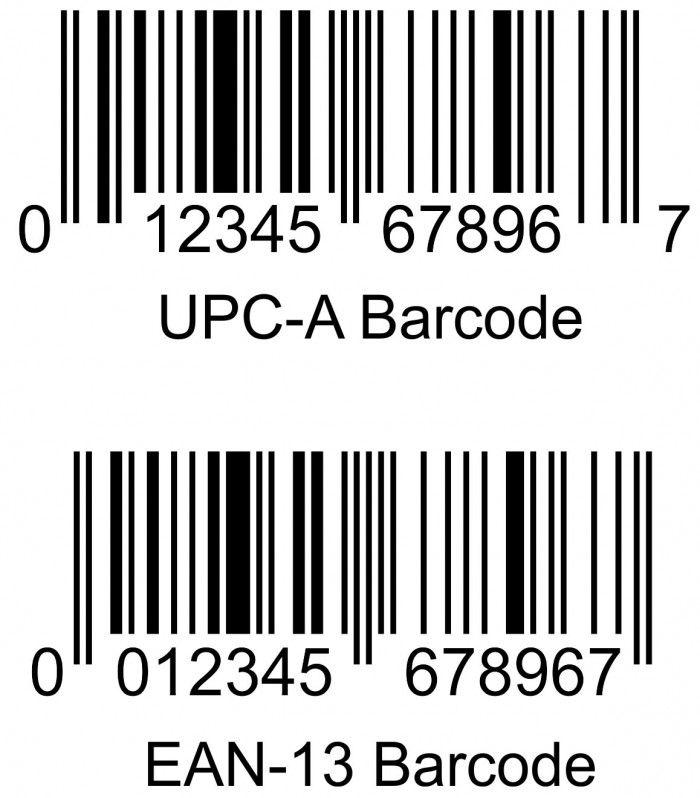

In addition, the EAN, or International Article Number, is different from the UPC just by way the way it is formatted or the visual appearance of the barcode, but it is no different in its encodings. Visually, the UPC code has the first and last number-encoded bar sequences extending below the bars that encode the other numbers, but the EAN barcodes have these two codes exactly the same height as the other encoded numbers. Notice in the illustration that the bars and spaces that encode each number are identical in the EAN-13 and UPC-A barcodes, but just the formatting of the outer bars differ. The entire family of International Article Numbers is differentiated by country or region by the first two to three numbers of the code. For instance, the UPC is always encoded with numbers 00-13 in these positions, whereas Japan always has the numbers 49 or 45, china uses the numbers 690-692, and India uses 890.

In addition, the EAN, or International Article Number, is different from the UPC just by way the way it is formatted or the visual appearance of the barcode, but it is no different in its encodings. Visually, the UPC code has the first and last number-encoded bar sequences extending below the bars that encode the other numbers, but the EAN barcodes have these two codes exactly the same height as the other encoded numbers. Notice in the illustration that the bars and spaces that encode each number are identical in the EAN-13 and UPC-A barcodes, but just the formatting of the outer bars differ. The entire family of International Article Numbers is differentiated by country or region by the first two to three numbers of the code. For instance, the UPC is always encoded with numbers 00-13 in these positions, whereas Japan always has the numbers 49 or 45, china uses the numbers 690-692, and India uses 890.

Regardless of the specific subtype being used, the GTIN is perhaps the most recognizable of all barcode formats simply because of its universal appearance on products that people buy on a daily basis. Its widespread use began with the endorsement of the UPC symbol by the grocery industry in the U.S. back in 1973. That one act caused barcode technology to quickly become a familiar aspect of American society. Throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s, grocery stores across the country installed laser scanners and automated cash registers to incorporate the UPC symbol into their operations. The result was huge savings in operational expenses—both in terms of the ease of inventory control and the increases in productivity at the checkout counter.

The UPC pioneers in the grocery industry may not have realized it at the time, but they started a revolution that promised to change the way people purchased all retail items. In fact, it wasn’t very long before many other retail goods besides groceries were also being marked with a UPC barcode. This ubiquitous symbol, or derivatives of it, now can be found on merchandise as diverse as food items, magazines, books, hardware, clothing, toys, and drugs. Today it is virtually impossible to find a retail item in the U.S. that isn’t marked with a UPC symbol.

At the same time the UPC was proliferating in the U.S., the other countries of the Western Alliance were standardizing on nearly identical barcode symbols to mark their products. The Western Alliance nations were coordinating these efforts with a view toward global electronic digital buying and selling, which would eventually become cashless as well. Europe and Japan decided to go with slightly altered forms of the UPC code to maintain their independence from the U.S. Today, using the GTIN symbols consisting of either the UPC, EAN, or JAN variants, cashiers only have to pass an item over the scanning window at the checkout counter—symbol side down or at least sideways accessible to the laser scanner—and the cost and identification of the product is automatically recorded.

Just as the prophecies in Revelation predicted, in the coming cashless society of the Beast people won’t be able to buy or sell anything without this identifying mark present on it. As amazing as this may sound, it is through the use of the GTIN symbols that the Empire of the Beast is beginning to fulfill the end times economic system exactly as the Apostle John prophesied. The key to tying together EFT, POS, the Mark of the Beast, and the Number of the Beast (666) into one coherent system is nothing less than the family of GTIN retail barcodes used throughout the world. To understand how this scenario will occur, the symbology of these barcodes must first be deciphered.

Like the Code 39 symbology discussed previously, all of the GTIN symbols also appear to be a series of vertical bars. As in all barcodes, these black and white bar patterns are used to represent unique strings of numbers that identify an item. However, the symbology used with the UPC, EAN, or JAN is completely different than any of the other barcodes in use today. Since this symbol was primarily designed for the retail market, the code had to take into consideration the informational needs of the grocery industry, department stores, hardware stores, and specialty shops all around the world. Whatever or wherever an item was sold, the GTIN barcode had to be designed to work as the common identifying mark globally.

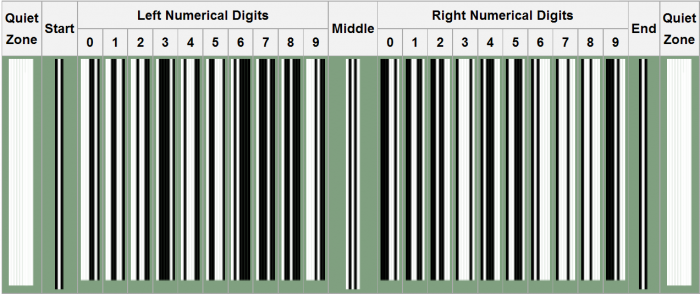

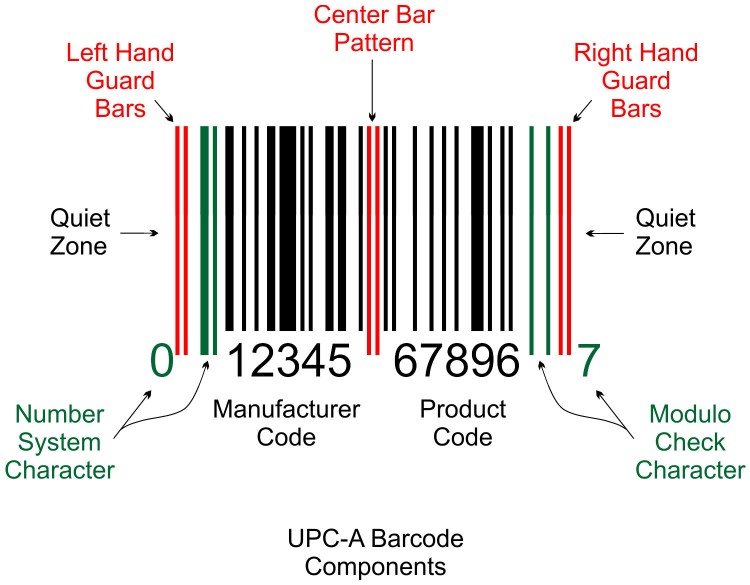

At first glance, it is apparent that the most common GTIN barcodes are divided into two distinct halves (see figures). These halves are separated by a thin double bar which runs vertically through the middle of the code. This center bar pattern, as it is called, normally extends farther down than the other bars adjacent to it and can be seen to almost completely separate the numbers written below the code. On a UPC, EAN, or JAN barcode, the numerals below the symbol are the human-readable interpretations of each digitally encoded number directly above. Each side of the basic U.S. UPC symbol has enough information to code for five digits plus one control code.

According to the convention set forth by the Universal Product Code Committee early in the UPC development, the left half of the symbol always contains the code identifying the product’s manufacturer or distributor. Thus, when a barcode mark is scanned, a computer system can know immediately the origin and manufacturer of a particular product. Each manufacturer or distributor is registered and assigned a different left side number by the organization called GS1, based in Brussels, Belgium, which administers all of the GTIN barcodes globally. This is also the same group that is developing the Electronic Product Code, which incorporates an RFID chip containing a much longer ID than is possible using barcodes alone (see the section on RFID for additional information).

Global control through GS1 of the manufacturer’s code on the left side of a GTIN symbol ensures that different barcoded items don’t inadvertently have the same manufacturer designation unless the products are truly made by the same company. In addition, in order to identify different products made by a given company, the right side of the UPC symbol is assigned a unique five-digit product number by its manufacturer. Thus, the GS1 organization first assigns the manufacturer’s number and then each company implementing a barcode assigns its own product numbers to the right side and registers the final code with GS1. This process results in a complete GTIN ID number that corresponds to each type of product sold. At least in theory, then, every unique retail item in existence can have its own product-related UPC, EAN, or JAN symbol to identify it according to its manufacturer and product number.

In fact, according to the GS1 General Specification document, this symbol on retail products is no longer optional:

“The EAN/UPC Symbology family of bar codes (UPC-A, UPC-E, EAN-13, and EAN-8 Bar Codes and the two- and five-digit Add-On Symbols) can be read omnidirectionally. These symbols must be used for all items that are scanned at the Point-of-Sale and may be used on other trade items” (Section 5.1, Version 13.1, Issue 2, Jul-2013; emphasis mine).

Thus, according to GS1’s own specifications, this barcode family has become a required facet of international commerce when goods are bought and sold in retail markets. Remember, John’s prophecy in the book of Revelation says that the Number of the Beast will be required for all buying and selling at the end (Rev. 13:18). Let’s look at the design of this symbol in more detail to see just how the number 666 figures into this picture.

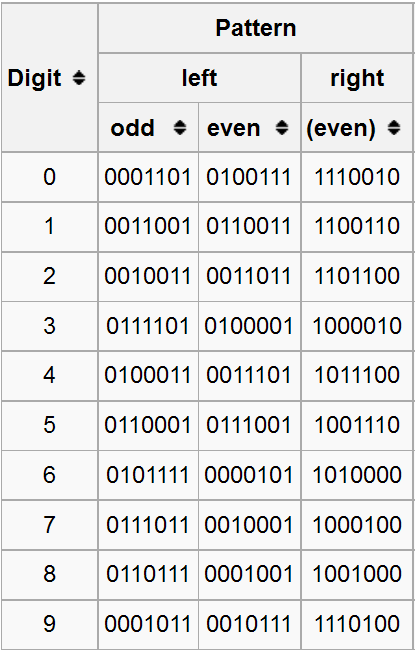

The EAN/UPC barcode is a linear symbol that is encoded with data much like other linear barcodes. However, unlike the Code 39 symbology described previously where 9 modules of information consisting of either white spaces or dark bars code for a particular character, the UPC symbol uses a pattern of 7 modules consisting of 2 black bars and 2 white spaces do the same job. The widths and positions of these bars and spaces determine which number is represented by the code. In reality, though, the full interpretation of the UPC symbol is a little more complex than this first impression of black bars and white spaces would suggest. It is also more complex in its design than Code 39.

The EAN/UPC barcode is a linear symbol that is encoded with data much like other linear barcodes. However, unlike the Code 39 symbology described previously where 9 modules of information consisting of either white spaces or dark bars code for a particular character, the UPC symbol uses a pattern of 7 modules consisting of 2 black bars and 2 white spaces do the same job. The widths and positions of these bars and spaces determine which number is represented by the code. In reality, though, the full interpretation of the UPC symbol is a little more complex than this first impression of black bars and white spaces would suggest. It is also more complex in its design than Code 39.

When a scanner interrogates a UPC symbol, it will actually sense within the bar patterns 7 “modules” of spatial information for each number encoded. In other words, each number of a UPC symbol is made up of 7 discrete bits of data designed within the black and white spaces representing each number. Each one of these modules is assigned a specific width within the code and the scanner and computer can differentiate these widths as digital information. The narrowest black bars that can be seen within a typical UPC barcode are exactly one module wide. The same goes for the narrowest white spaces. In addition, the black bars or white spaces can be 1, 2, 3, or 4 modules wide when encoding for a particular number. As the scanner encounters one of these modules or bits of information, it sends to the computer either a binary “1” or a “0” depending on whether the module happens to be within a black bar or a white space, respectively (see figure). Each character is built from a sequence of 7 such modules of information, and thus a string of 1’s and 0’s results from a complete scan.

There are also other important parts to the EAN/UPC symbol that we need to understand. In addition to the bars corresponding to the basic ten-digit code for each UPC, there are bars immediately to the outer sides of the manufacturer and product code regions which do not have numbers directly below them. Just to the outer left of the left-hand manufacturer’s code, there is a set of bars that usually extend farther down than the main part of the symbol. The human-readable number that these bars represent can usually be seen standing alone and centered off to the left side in the margin. This part of the symbol is occupied by a special code called the number system character, and it can have a value from zero to nine.

With the addition of this bar pattern, the UPC actually becomes an eleven-digit code. However, this character is usually not used in the same manner as the main part of the symbol. Instead of coding for a particular manufacturer or product, this number is reserved for categorizing special uses of the UPC code in retail commerce. The function of this number is simply to identify to the computer what type of UPC symbol is currently being scanned. Since there are many potential areas where the UPC may find application, the number system character has been developed to effectively differentiate each category as the barcode is read.

In the standard form of the UPC (called UPC-A), there is always a zero that is encoded in the number system character position. This standard form is the type typically used for most retail products and the overall barcode is symmetrical in appearance. However, in addition to this basic form, the National Drug Code and the National Health Related Items Code both use a UPC symbol which has a number system character of “3” in this first position. Likewise, a UPC-compatible code called the Distribution Symbol always appears with a “4” as the number system character, while a “5” would refer to the use of a UPC on a coupon. Thus, one coding system can have many different fields of retail application, but the symbology will be able to tell a computer exactly what type of code is meant with the appropriate use of the number system character.

Since the UPC-A symbol is basically divided down the middle in symmetry; you can move similarly to the immediate right of the product encoding region and encounter another set of two black bars which have no apparent label below them. Just like the number system character, these bars also extend below the plain of the main 10-digit code. In this case, however, the bars are not usually identified by a number either below or off to the right. Only on rare occasions will this particular portion of the UPC be treated as a twelfth character which would appear in human-readable form, usually off to the lower right of the symbol. This infrequent situation is typically seen in the U.S. when the UPC is used for encoding a coupon. Thus, the UPC has the capability of becoming a twelve-digit mark that is divided down the middle by the center bar pattern—ultimately giving it two six-character data fields.

However, the twelfth digit on the far right is actually not read in the same manner as the rest of the code. Rather, these bars normally code for something called the modulo check character. This check digit is used to verify the accuracy of the scanning process on the rest of the code. The correct reading of the modulo check character can be calculated from the preceding ten digits through the use of a special mathematical formula for parity. When a barcode is scanned, the computer quickly calculates the check digit from the proceeding numbers, and if the calculation doesn’t match the modulo check character, then the scanner indicates an error and the barcode can be scanned again. In a checkout lane, this error can be heard as an audible sound that is distinct from the typical beep of a correctly read barcode or it may result in no beep at all. The use of a check digit to verify the reading of barcodes for retail purchases can result in scanning accuracies that are far above 99.9%.

At this point, all parts of the UPC that code for particular numbers within the symbol have been identified. However, there are still two bar patterns that have not been considered. As you approach the UPC from the far right or far left, the first bar pattern encountered visually appears to consist of two thin black lines, each exactly one module wide. These bars, like the modulo check character, the center bar pattern, and the number system character, also extend below the plain of the other ten digits. Unlike the other two special characters on the right and left sides, however, the outer bars and the central bars have no apparent numerical equivalents written in human readable form on the symbol. Visually, they all appear to be the same type of bar pattern containing two thin black bars separated by thin white spaces. These three sets of bars, however, are distinct from the rest of the symbol and do not code for numbers. The outer two sets of bars are called the left-hand and right-hand guard bars and function as the start and stop characters of the symbol, whereas the center bar pattern divides the EAN/UPC down the middle.

At this point, all parts of the UPC that code for particular numbers within the symbol have been identified. However, there are still two bar patterns that have not been considered. As you approach the UPC from the far right or far left, the first bar pattern encountered visually appears to consist of two thin black lines, each exactly one module wide. These bars, like the modulo check character, the center bar pattern, and the number system character, also extend below the plain of the other ten digits. Unlike the other two special characters on the right and left sides, however, the outer bars and the central bars have no apparent numerical equivalents written in human readable form on the symbol. Visually, they all appear to be the same type of bar pattern containing two thin black bars separated by thin white spaces. These three sets of bars, however, are distinct from the rest of the symbol and do not code for numbers. The outer two sets of bars are called the left-hand and right-hand guard bars and function as the start and stop characters of the symbol, whereas the center bar pattern divides the EAN/UPC down the middle.

Some type of outer guard bars are usually found at the beginning and end of most barcode symbologies. These special characters tell the computer that a barcode scan is about to take place and also let the computer know from which direction the read will occur. In other words, the start and stop characters allow a UPC to be read from either the right or the left, while still transmitting the proper information. These outer guard bars are always preceded by what is known as a “quiet zone”. This is nothing more than white space of at least seven modules wide which is designed to isolate the UPC from anything else that may be printed on a package.

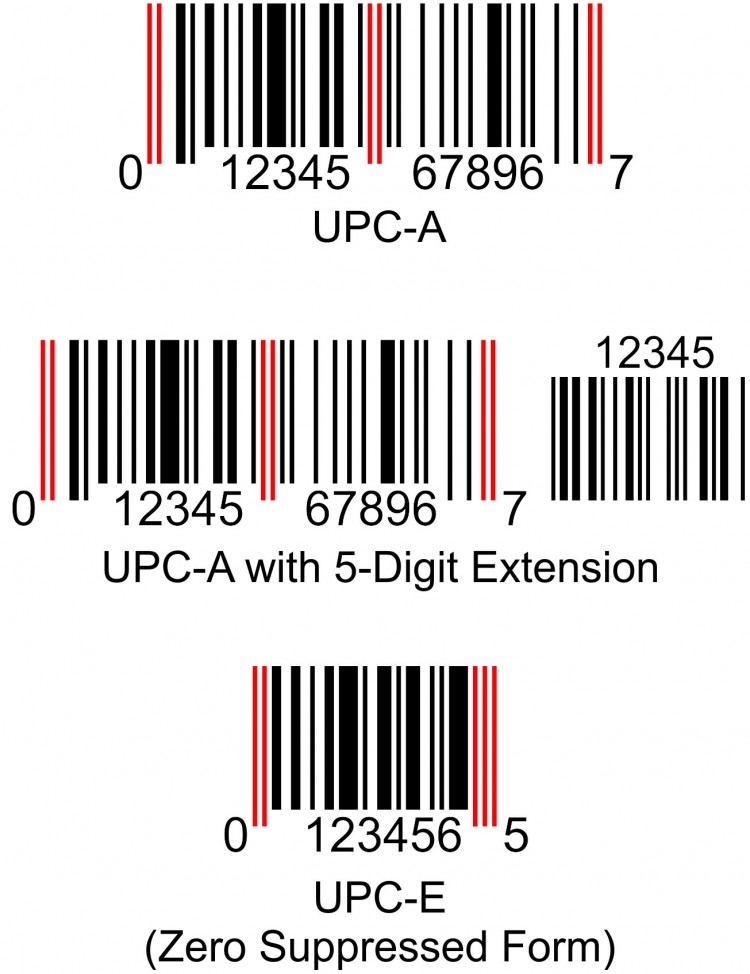

There are three different ways in which the UPC can appear to the naked eye (see figure). All three of these forms contain the same three control patterns found on the standard UPC, namely guard bars at the beginning and end of the symbol and a central bar pattern which divides the main parts of the code. However, one quick look at the so-called “zero suppressed” version of the UPC and it may seem like that statement is not entirely true. The zero suppressed UPC (also called “Version E”) is used when a manufacturer has a limited number of products (and thus the right side of the code turns out to be mostly zeros) or when there is not enough space on a package to accommodate the full code. Version E actually has all three of these control patterns present, but it possesses them in a slightly different configuration (more on this in a moment).

A third form of the standard UPC can be found when the standard code is accompanied by either a two- or a five-character supplemental encodation. These added codes are designed to allow for more information to be included when the symbol appears on periodicals or paperback books. Even though this third configuration has extra bars off to the right side of the code, the standard UPC is still present with its two guard bar patterns and one center bar pattern.

The Number 666 in Retail Barcodes

What in the world could be so significant about the presence of three control patterns in every UPC symbol? The answer to that question is fascinating, but to uncover the secret, the binary sequences that code for the numerals 0-9 in the three forms of the UPC must be first interpreted.

Unlike other linear barcode symbols, the UPC actually uses several different binary interpretations for each character. These different codes for the numbers zero through nine are called set A, set B, and set C elements. It turns out that the binary sequence used for any one particular number is dependent upon where the number appears within the UPC code. This means that with regard to the standard UPC symbol, the manufacturer code (left side) and the product code (right side) actually use different bar code patterns to refer to the same number. Set A elements are used on the left side of the UPC and set B elements are used on the right side of the standard UPC-A barcode. The accompanying table shows these seven bit binary codes and how they differ between the two sides of the symbol.

Unlike other linear barcode symbols, the UPC actually uses several different binary interpretations for each character. These different codes for the numbers zero through nine are called set A, set B, and set C elements. It turns out that the binary sequence used for any one particular number is dependent upon where the number appears within the UPC code. This means that with regard to the standard UPC symbol, the manufacturer code (left side) and the product code (right side) actually use different bar code patterns to refer to the same number. Set A elements are used on the left side of the UPC and set B elements are used on the right side of the standard UPC-A barcode. The accompanying table shows these seven bit binary codes and how they differ between the two sides of the symbol.

Remember that each number in a UPC symbol is visually seen as two bars and two spaces and their thickness and position within the total seven module sequence is what encodes each character. Therefore, all zeros within the binary code will appear to the eye as white spaces and all ones will show up as black bars. In addition, the number of white space modules (zeros) or black bar modules (ones) that occur side-by-side determines the thickness of each bar or space. One other aspect of the code to point out is that the binary equivalents of numbers on the left side always have an odd number of black bar modules (called odd parity), while all the right-side codes consist of an even number of black bar modules (even parity). In addition, the left-side codes all begin with a white space (zero) and the right-side codes all begin with a black bar (one).

To make matters a little bit more complicated, Version E of the symbol uses the same binary codes which appear on the left side of the standard UPC, but it does not use those which code for the right side. Instead of drawing from the same right-hand codes, the zero-suppressed symbol uses a third set of binary digits which are generated by exactly reversing the codes for the right side of the standard UPC. In other words, referring to the table, the binary equivalent for the number 5 from set B—appearing on the right-hand side of the standard symbol and represented by the sequence 1001110—becomes 0111001 in the UPC Version E barcode. Similarly, the number 7 goes from 1000100 on the right side of the standard UPC to 0010001 when used in the zero-suppressed form.

Thus, the number of UPC binary codes that identify the numbers 0-9 is in reality 30. This total comes from the 10 codes from set A which code for the left side on the standard design, 10 from set B which code for the right side, and 10 from the zero-suppressed version (set C) which are just the mirror image or reverse of set B codes. These different binary codes for the different sides or designs of the UPC barcode ensure that it can be scanned from any direction and the proper identification number still can be determined by the computer system.

In addition, Version E is precisely one-half of the standard UPC barcode design. Therefore, instead of having two data fields of six digits each, the zero-suppressed form has two data fields of three digits each. The data fields are differentiated from one another by having three numbers coded from set A of the binary equivalents and three numbers coded using set C. Also, unlike the standard UPC which has the center bar pattern directly in the middle of the symbol to divide the six-digit fields, Version E has this control character appearing at the end of the symbol just before the stop character. In this case, however, the center bar pattern also is reduced to one-half the size it normally appears in the standard UPC-A symbol. Therefore, even in the “condensed” version all three control characters are still present—the center one just has half its normal bar patterns.

This fact is important because it is from knowledge of the binary encoding for these control characters that the prophetic significance of the UPC symbol finally becomes apparent. Unlike the codes for numbers in the main body of the symbol, the control characters are not full seven-bit binary codes. The reason for this difference is to maintain their uniqueness so that a scanner does not wrongly interpret them as numbers. In fact, each guard bar pattern is only a three-bit binary code, while the center bar pattern is a five-bit binary code (see figure). Visually, however, all three control characters appear exactly the same to the naked eye. This is due to the fact that the basic binary pattern “101” is present in each of them. For this reason, when you look at each control character, they all appear as two thin black bars—even though the scanner is able to interpret their subtle differences from encoded numbers due to the fewer number of modules present.

This fact is important because it is from knowledge of the binary encoding for these control characters that the prophetic significance of the UPC symbol finally becomes apparent. Unlike the codes for numbers in the main body of the symbol, the control characters are not full seven-bit binary codes. The reason for this difference is to maintain their uniqueness so that a scanner does not wrongly interpret them as numbers. In fact, each guard bar pattern is only a three-bit binary code, while the center bar pattern is a five-bit binary code (see figure). Visually, however, all three control characters appear exactly the same to the naked eye. This is due to the fact that the basic binary pattern “101” is present in each of them. For this reason, when you look at each control character, they all appear as two thin black bars—even though the scanner is able to interpret their subtle differences from encoded numbers due to the fewer number of modules present.

As mentioned previously, in Version E the position of the center bar pattern is different. It appears merged with the right-hand guard bars, and, because of this situation, the total character takes on the binary form “010101”. This code results from the fact that the center bar pattern is halved in the zero-suppressed version just like the whole symbol is halved. In a sense, then, the center bar pattern and the right-hand guard bars “share” the central binary “1”. Since the computer is able to interpret the zero-suppressed version as a full ten-digit UPC (because the missing right side numbers are all zeros, thus it is called “zero-suppressed”), the halved center bar pattern turns out to be just part of the abbreviation for the full code.

Why is this configuration of the control codes so significant in an EAN/UPC mark? Take a quick look at the binary interpretation for the number six as it appears in either set B or set C. Notice that the same “101” pattern is present in both binary code sets. Now look at any retail products that are marked with a UPC-A symbol and look on the right side for a number six (which uses set B of the code). Some barcodes will have a 6 on the right side and some won’t, depending on the product number chosen by the manufacturer. However, if it contains a 6 on the right side, you will see that visually all three control codes look identical to the double-bar pattern representing this number from set B. Thus, from a visual perspective, the basic double black bar pattern for the number 6 is present in every UPC exactly three times. To say this a little differently, every retail product is now being marked with a bar code that visually appears to contain the number 666!

Why is this configuration of the control codes so significant in an EAN/UPC mark? Take a quick look at the binary interpretation for the number six as it appears in either set B or set C. Notice that the same “101” pattern is present in both binary code sets. Now look at any retail products that are marked with a UPC-A symbol and look on the right side for a number six (which uses set B of the code). Some barcodes will have a 6 on the right side and some won’t, depending on the product number chosen by the manufacturer. However, if it contains a 6 on the right side, you will see that visually all three control codes look identical to the double-bar pattern representing this number from set B. Thus, from a visual perspective, the basic double black bar pattern for the number 6 is present in every UPC exactly three times. To say this a little differently, every retail product is now being marked with a bar code that visually appears to contain the number 666!

This basic 666 pattern from the beginning, middle, and end of the UPC/EAN barcode turns out to be the principal control code for the entire system to properly operate. It’s amazing how this situation has developed, because the inventors of the UPC design didn’t have to use a variation of the number six for the control codes. They could have used a truncation of any of the other binary codes that identify a number. In fact, they could have developed a completely unique bar pattern just for the control codes alone. With seven-bit encoding, there’s a possibility of developing many additional bar patterns. Why did they choose a variation of the number six when other potential patterns exist?

It is uncanny the way the GTIN mark fulfills Biblical prophecy. In fact, everything about the EAN/UPC/JAN barcode symbols speak of the number six: A pseudo 666 makes up the control patterns, a left side code comprises a six-digit field for the UPC type and manufacturer, a six-digit right side code is used for the product and modulo check character, and a condensed version of the symbol exists with only a single six-digit field. Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of this revelation is the fact that the Empire of the Beast is developing the Number of the Beast even before the rise of the Antichrist. In recent decades the world has become accustomed to using these barcodes to purchase virtually any product available for retail sale.

Barcodes and the Mark

Revelation 13:18 is a prophecy of the Mark of the Beast, the Number of the Beast, and the Name of the Beast; all of which are predicted to be used in conjunction with buying and selling at the end. The Greek word translated as the word mark in this verse is charagma. According to Strong’s Greek Concordance, charagma means “an engraving (etching), a mark providing undeniable identification, like a symbol giving irrefutable connection between parties”. The digital ID marks that will be used to brand people and things in the Antichrist’s kingdom will serve to validate identities in order to participate in the electronic cashless society of the one world empire. Without having the mark in the hand or the forehead to validate personal identity or the 666 barcode mark on all products, you will not be approved to buy or sell anything. In ancient times, a charagma was an impress on an official coin or an imprint on a wax seal validating the authenticity of a document. In the last days, the charagma mark on people and things will serve to validate, monitor, and approve all transactions.

In an amazing coincidence, the word charagma comes from the same origin as the word charax in the Greek. According to Strong’s Greek Concordance, a charax is “a pointed stake, a rampart”, or “a palisade”. A palisade is a fence or a stakewall that is typically made of wooden stakes placed together vertically to make a partition or a wall, especially for defense (see illustration). A modern day structure like this might be called a picket fence. Isn’t it incredible that an ancient palisade has an amazing similarity to the vertical bars of a barcode? Could it be that even the origin of the very word used in Revelation associated with the Mark is trying to point us in the direction of correctly identifying the UPC/EAN barcode as the fulfillment of prophecy? Could it also be that the barcode containing the number 666 will ultimately be merged with the Mark of the Beast and that the final mark will be a UPC/EAN type of barcode placed on all the followers of the Antichrist (see The Mark of the Beast for additional information)?

In an amazing coincidence, the word charagma comes from the same origin as the word charax in the Greek. According to Strong’s Greek Concordance, a charax is “a pointed stake, a rampart”, or “a palisade”. A palisade is a fence or a stakewall that is typically made of wooden stakes placed together vertically to make a partition or a wall, especially for defense (see illustration). A modern day structure like this might be called a picket fence. Isn’t it incredible that an ancient palisade has an amazing similarity to the vertical bars of a barcode? Could it be that even the origin of the very word used in Revelation associated with the Mark is trying to point us in the direction of correctly identifying the UPC/EAN barcode as the fulfillment of prophecy? Could it also be that the barcode containing the number 666 will ultimately be merged with the Mark of the Beast and that the final mark will be a UPC/EAN type of barcode placed on all the followers of the Antichrist (see The Mark of the Beast for additional information)?

When the Apostle John prophesied of the number 666, he said that the final world system would absolutely require it to buy or sell—of course, along with having the Mark of the Beast and the Name of the Beast. How close do you think we are to the Return of Christ seeing that these prophecies are coming to pass in our day?

However, barcodes are not the only way that the number 666 is being used in commerce today. Along with the marking of all products with a pseudo 666-containing code, the electronic computer systems making up the Internet also use another instance of 666 to make electronic buying and selling possible. In the next section, we will see how Web-based commerce actually depends on this number for secure online transactions to occur.

Next: Security Permissions Setting 666