German Reunification

The most unexpected and significant expansion of the EC occurred in 1990 as a result of the crumbling of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of communism across Eastern Europe. The resultant reuniting of East and West Germany into a new super-state promised to dramatically affect the course of world events. This expansion did two things. It created the most powerful nation within the EC and elevated the union to a point where at least potentially they could become the greatest political, economic, and military force the world has ever seen. With the addition of East Germany, the EC then had over 343 million people, compared with 240 million in the U.S at that time. The new growth in the European alliance could now become the seed to the creation of a new world order on a global scale.

Terrance Petty of the Associated Press said that “even with the shocks and economic burdens of unification, the new Germany of 80 million people is an economic powerhouse astride central Europe.” He adds, “Now they have confidently taken the lead in European affairs, giving them the most dominant position they have had on the continent since Adolf Hitler’s defeat in 1945” (Associated Press, 10/6/91).

Of course the new reunified Germany raised old fears among its neighbors, especially the British and the French. For the third time in the Twentieth Century, a united Germany has risen to clear European dominance. Even before the reunification, West Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP) represented about one-fourth of the EC’s total GDP. If Germany now decided to become a military superpower as well as an economic one, they could easily monopolize the entire European continent. The smaller nations of Europe had every right to be concerned.

Germany’s stated goal, however, was not to recreate the darkest hours of their history, but to further support European cooperation and integration. With a united Germany at the helm, the EC could soon have more influence than the U.S. on the world political and economic scene. All that was lacking was unity and leadership for the overall community, but even that would change.

The Maastricht Treaty

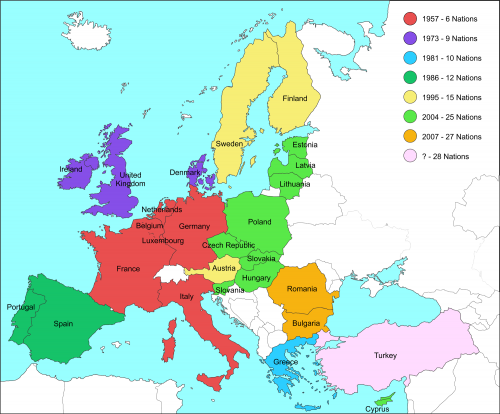

In an historic meeting in Strasbourg in late 1989, the EC again agreed to press ahead toward complete political, economic, and monetary union. Their initial objective was to transform the 12 countries into one barrier-free market. Although there were serious reservations concerning the plan by several EC partners, the highly ambitious goal was legitimized in December of 1991 when the community finalized a new treaty.

The articles of this new constitution established the basis for a new European Union (EU), which began functioning on January 1, 1993 (the Maastricht Treaty). Actually, 1993 was only the target for creating a true common market devoid of trade barriers; however, the new constitution went far beyond that simple beginning—no less than complete economic, political, and military integration was in view for the 1990’s.

For instance, soon the European Parliament, which had grown to 518 members, would have the right to make community law. The political consequences of this change brought under EU jurisdiction such affairs as health, education, energy, environment, trade and cultural issues, tourism, consumer and civil laws, and industrial regulations. The EU began to develop common policies relating to every issue and activity which transcends the borders of its member nations. This supranational jurisdiction of major departments within the community started to resemble the major Federal departments within the U.S. government.

The architects that were moving Europe toward full integration in the 1990’s hoped that any nationalistic concerns would be overcome by the advantages of economic and political union. U.S. News & World Report had said, “…an integrated EC alone can come close to equaling America’s $5.2 trillion economy” (U.S. News & World Report, 11/27/89). Throw in a united and prosperous Germany as the leader of this new Europe and the EC had potential to become the primary arbiter of all world trade and commerce.

Even with these major accomplishments toward greater European unity, there still were significant concerns over establishing a Federal European Government. Britain especially feared that any move toward federalism would erode the powers of the individual nations, effectively eliminating national sovereignty. Britain was perhaps the most vocal opponent of a united Europe, which probably resulted from a history of mistrust toward France and Germany. However, the Brits were not alone. The Maastricht treaty had to be ratified by all twelve member states before it could be fully instituted. According to the Treaty of Rome, if even one nation rejected an EC proposal, a proposition could not be established.

On June 2, 1992, Denmark put the Maastricht treaty to popular vote. By a margin of only 46,000 votes the referendum failed. The ramifications of that narrow rejection reverberated around the world. Suddenly, all the grand plans of the political leaders of Europe were ground to a halt. Panicked treaty backers met in closed-door meetings all over the EU to try to figure out a solution to the annoying Danes. The architects of a united Europe, however, were determined not to let that setback deter their schemes. Some called for another vote in Denmark after extensive lobbying for the treaty in the media. Others said that Denmark ultimately could be kicked out of the EU. Still others called for the immediate monetary integration of Germany, France, and Italy—effectively unifying the currency of most of the EU without treaty approval. As the forces in Europe were moving toward the first economic and political unification since the Roman Empire fell, the counter forces of individual nationalism were keeping them apart.

Eventually, in early 1993 Denmark again put the Maastricht Treaty to a vote. This time the EU leaders promised them significant consolations if they would only ratify it. The treaty passed. Only Britain remained a solid bastion of opposition to the new European Union, but they still remained a part of the alliance.

The prophet Daniel had predicted that the initial rise of the Beast would involve a “partly strong and partly broken” alliance of nations, and this is exactly what Europe has experienced. The headline of The European, a popular EU newspaper, probably summed it up best: “Europe—A Unity Built in Sand” (The European, June 11, 1992). In Daniel’s interpretation of the ten toes of Nebuchadnezzar’s image, the feet consisted of the strength of iron, but mixed with clay so that the parts couldn’t completely stick together. The rocky road of European integration in the Twentieth Century has paralleled the Biblical predictions with uncanny precision. And as the Bible also predicts, that road will not be smoothed out until the rise of a powerful leader able to capture the hearts and minds of the entire world.

With the fall of the Soviet Union and capitalism breaking out across all of Eastern Europe, the influence of the EU rapidly grew. The new Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) which replaced the Soviet Empire was looking toward the EU for advice and aid to move quickly to a market economy. Also, several nonmember Eastern European countries wanted closer ties with the EU to avoid any re-association with Russia. One article predicted the situation might evolve like this:

“Most likely, Europe after 1992 will grow both broader and deeper. Europe could come to resemble a series of concentric circles, EC President Delors theorizes, with the European Commission in the middle and other countries in more distant rings with less comprehensive ties. In the outer rings, according to this theory, would be members of the European Free Trade Association—Austria, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.” (U.S. News & World Report, 11/27/89).

And just as predicted, in a historic accord in October of 1991, the EU officially teamed up with the seven nations of the European Free Trade Association to form the largest common market on the globe. The name for the new association was the European Economic Area, creating the first “concentric circle” of EU influence. By the early-1990s, it quickly became the most lucrative of all consumer markets, accounting for over 40% of world trade (Associated Press reports, 10/24/91).

The potential for a European new world order was enormous. One report said, “There are 500 million people in Greater Europe, with nearly 360 million in Western Europe alone. Economically, Western Europe already is a superpower. Its gross domestic product is $5.5 trillion, about 70% of the GDP of the U.S. and Japan combined” (U.S. News & World Report, 11/27/89).

There also was talk of more serious steps toward a common defense policy far exceeding that of NATO. For years Western Europe wasted considerable money, because the arms industries within the member nations duplicated each other’s efforts. The Economist had said, “…there ought to be a more-or-less unified European defense establishment…which could talk to the United States on equal terms” (Economist, May, 19, 1984, p.55). Suggestions had been made that proposed all EU nations could help finance the continued development and deployment of the British and French nuclear forces. It was also possible that a united Germany could quickly join the nuclear club. In this way, the community would be considered a true superpower—one able to stand on equal footing with the U.S., Russia, and China. Ironically, one of the major proponents of a European Defense Union at that time was France, the same country which originally vetoed such suggestions back in the late 1940’s.

A NATO meeting in late 1991 centered on creating a new role for the Atlantic alliance. The vision was to form a pan-European security institution that would encompass not just the west, but Eastern Europe as well. The broader group would be assigned the task of assuring peaceful relations among all the countries from Iceland to Turkey and with influence far beyond. At the center of this new security alliance would be the EU.

Already the EU had begun to flex its muscle. The civil war in Yugoslavia between ethnic factions was being almost ignored internationally until the EU got involved. At first the community tried diplomatic initiatives involving several failed cease fires. Next, trade and economic sanctions were implemented by the EU, including an oil embargo coupled with a limited United Nations military presence to insure the peace. The EU was beginning to take on an international role similar to that of the U.S., but in concert with the U.N. and America.

Not surprisingly, the EU nations were the main proponents of creating a “new world order” complete with economic and military muscle to enforce U.N. decisions. The EU had discovered dramatic new power on the world political scene. Muscle flexing on behalf of Europe had only just begun.

By the middle of the 1990s, in every respect it appeared that the EU was working toward the unified confederation that would make it a true fulfillment of Biblical prophecy. European leaders like Ernest Wistrich were convinced it would unite: “By the end of the century, we will have a European union with a clear identity” (Chicago Tribune, Mar. 18, 1984, Sec. 1, p. 6).

Next: The Group of Seven